Dyadic transformation

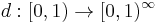

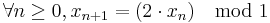

The dyadic transformation (also known as the dyadic map, bit shift map, 2x mod 1 map, Bernoulli map, doubling map or sawtooth map[1][2]) is the mapping (i.e., recurrence relation)

produced by the rule

.

.

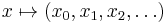

Equivalently, the dyadic transformation can also be defined as the iterated function map of the piecewise linear function

The name bit shift map arises because, if the value of an iterate is written in binary notation, the next iterate is obtained by shifting the binary point one bit to the right, and if the bit to the left of the new binary point is a "one", replacing it with a zero.

The dyadic transformation provides an example of how a simple 1-dimensional map can give rise to chaos.

Contents |

Relation to tent map and logistic map

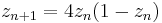

The dyadic transformation is topologically conjugate to :

- the unit-height tent map

- the chaotic r=4 case of the logistic map.

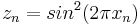

The r=4 case of the logistic map is  ; this is related to the bit shift map in variable x by

; this is related to the bit shift map in variable x by

.

.

There is semi-conjugacy between the dyadic transformation ( here named doubling map) and the quadratic polynomial.

Periodicity and non-periodicity

Because of the simple nature of the dynamics when the iterates are viewed in binary notation, it is easy to categorize the dynamics based on the initial condition:

If the initial condition is irrational (as almost all points in the unit interval are), then the dynamics are non-periodic—this follows directly from the definition of an irrational number as one with a non-repeating binary expansion. This is the chaotic case.

If x0 is rational the image of x0 contains a finite number of distinct values within [0, 1) and the forward orbit of x0 is eventually periodic, with period equal to the period of the binary expansion of x0. Specifically, if the initial condition is a rational number with a finite binary expansion of k bits, then after k iterations the iterates reach the fixed point 0; if the initial condition is a rational number with a k-bit transient (k≥0) followed by a q-bit sequence (q>1) that repeats itself infinitely, then after k iterations the iterates reach a cycle of length q. Thus cycles of all lengths are possible.

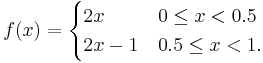

For example, the forward orbit of 11/24 is:

which has reached a cycle of period 2. Within any sub-interval of [0,1), no matter how small, there are therefore an infinite number of points whose orbits are eventually periodic, and an infinite number of points whose orbits are never periodic. This sensitive dependence on initial conditions is a characteristic of chaotic maps.

Solvability

The dyadic transformation is an exactly solvable model in the theory of deterministic chaos. The square-integrable eigenfunctions of the associated transfer operator of the Bernoulli map are the Bernoulli polynomials. These eigenfunctions form a discrete spectrum with eigenvalues  for non-negative integers n. There are more general eigenvectors, which are not square-integrable, associated with a continuous spectrum. These are given by the Hurwitz zeta function; equivalently, linear combinations of the Hurwitz zeta give fractal, differentiable-nowhere eigenfunctions, including the Takagi function. The fractal eigenfunctions show a symmetry under the fractal groupoid of the modular group.

for non-negative integers n. There are more general eigenvectors, which are not square-integrable, associated with a continuous spectrum. These are given by the Hurwitz zeta function; equivalently, linear combinations of the Hurwitz zeta give fractal, differentiable-nowhere eigenfunctions, including the Takagi function. The fractal eigenfunctions show a symmetry under the fractal groupoid of the modular group.

Rate of information loss and sensitive dependence on initial conditions

One hallmark of chaotic dynamics is the loss of information as simulation occurs. If we start with information on the first s bits of the initial iterate, then after m simulated iterations (m<s) we only have (s-m) bits of information remaining. Thus we lose information at the exponential rate of one bit per iteration. After s iterations, our simulation has reached the fixed point zero, regardless of the true iterate values; thus we have suffered a complete loss of information. This illustrates sensitive dependence on initial conditions—the mapping from the truncated initial condition has deviated exponentially from the mapping from the true initial condition. And since our simulation has reached a fixed point, for almost all initial conditions it will not describe the dynamics in the qualitatively correct way as chaotic.

Equivalent to the concept of information loss is the concept of information gain. In practice some real-world process may generate a sequence of values { } over time, but we may only be able to observe these values in truncated form. Suppose for example that

} over time, but we may only be able to observe these values in truncated form. Suppose for example that  = .1001101, but we only observe the truncated value .1001 . Our prediction for

= .1001101, but we only observe the truncated value .1001 . Our prediction for  is .001 . If we wait until the real-world process has generated the true

is .001 . If we wait until the real-world process has generated the true  value .001101, we will be able to observe the truncated value .0011, which is more accurate than our predicted value .001 . So we have received an information gain of one bit.

value .001101, we will be able to observe the truncated value .0011, which is more accurate than our predicted value .001 . So we have received an information gain of one bit.

See also

References

- ^ Chaotic 1D maps, Evgeny Demidov

- ^ Wolf, A. "Quantifying Chaos with Lyapunov exponents," in Chaos, edited by A. V. Holden, Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Dean J. Driebe, Fully Chaotic Maps and Broken Time Symmetry, (1999) Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht Netherlands ISBN 0-7923-5564-4

- Linas Vepstas, The Bernoulli Map, the Gauss-Kuzmin-Wirsing Operator and the Riemann Zeta, (2004)